NATIONWIDE – As summer heat waves intensify across the country, they are exposing a critical, often invisible, vulnerability in American cities: the legacy of their own design. The way cities were built, whether a century ago or in the last decade, is now determining who is most at risk when temperatures soar, revealing how decisions of the past create the public health crises of the present.

- Historical Disinvestment – Historically redlined neighborhoods in older industrial cities like Cleveland experience significantly higher temperatures due to a lack of green space and a concentration of heat-absorbing surfaces.

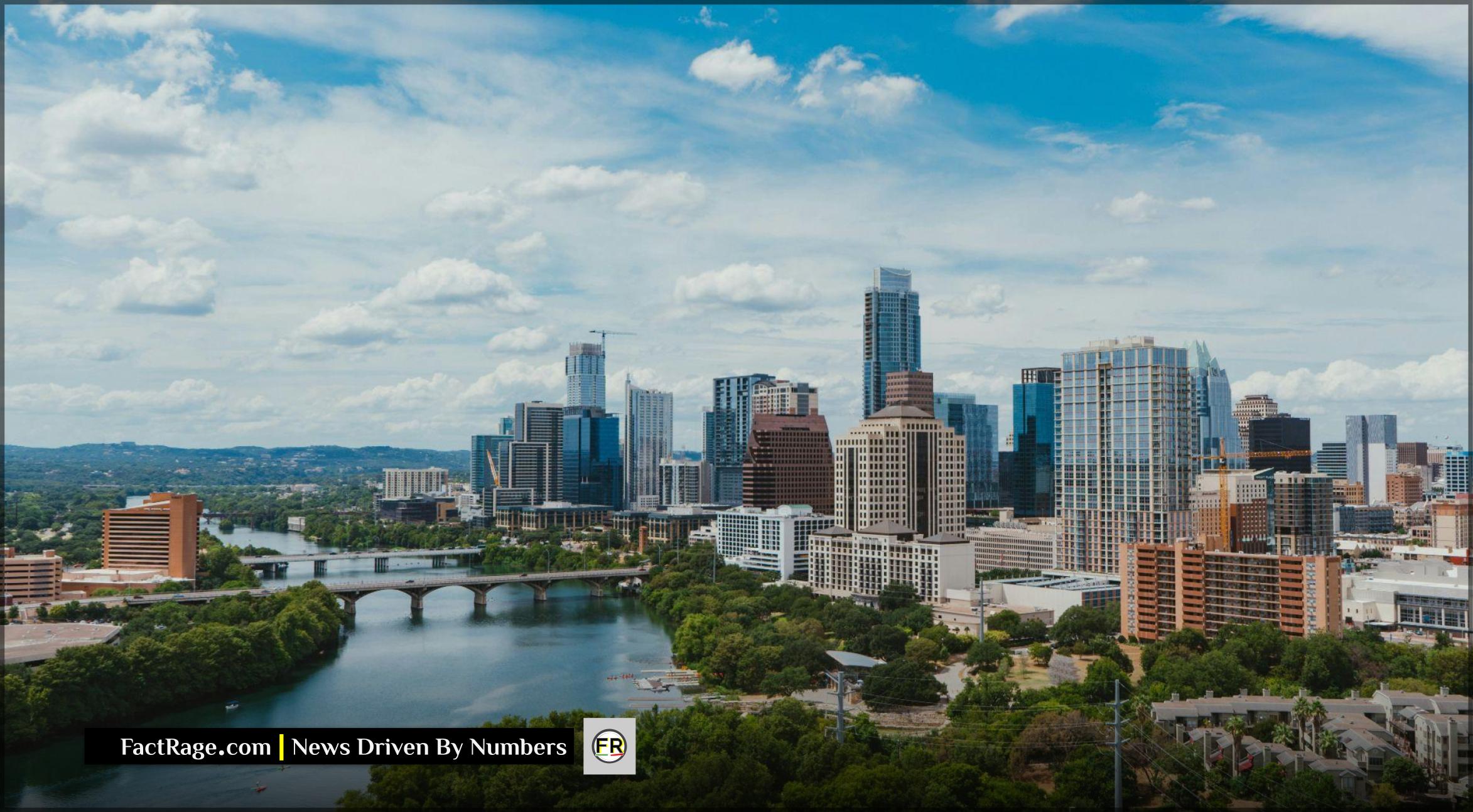

- Modern Growth Pressures – Rapidly growing Sun Belt cities like Austin face a different but related challenge, where modern urban sprawl and car-centric development create vast, new ‘heat islands.’

- A Common Consequence – In both models of urban development, low-income residents and communities of color disproportionately bear the brunt of life-threatening heat, a phenomenon known as ‘heat inequity.’

The story of a heat wave in America is a tale of two cities, represented by the historical challenges of the Rust Belt and the modern pressures of the Sun Belt. By examining the urban planning DNA of Cleveland, Ohio, and Austin, Texas, a clear picture emerges of how a city’s growth directly impacts its resilience to extreme heat.

The Weight of History: How Redlining Baked Heat into Cleveland

In Cleveland, once known as “The Forest City,” the danger of a heat wave is deeply rooted in 20th-century policy. Decades of industrialization followed by “white flight” and the racist 1930s federal housing policy of redlining have left a lasting scar on the city’s landscape. These policies systematically choked off investment in predominantly Black neighborhoods, particularly on the city’s east side.

The consequences are now dangerously clear. What were once thriving, tree-lined streets saw their canopy disappear. Since the 1950s, Cleveland has lost about half of its tree cover, with the city’s canopy now standing at a sparse 18%. Research shows a direct overlap between the neighborhoods redlined 80 years ago and the city’s most intense urban heat islands today. These areas can be up to 7 degrees warmer than the Ohio average and suffer from higher rates of pollution.

This isn’t just an issue of comfort; it’s a public health crisis. The same communities with the least tree cover also exhibit higher rates of chronic health conditions like asthma and diabetes, which are severely aggravated by extreme heat. For these residents, the heat doesn’t just arrive with the summer; it rises from the pavement and concrete that replaced a forest, a legacy of decisions made long before they were born.

The Price of Progress: Austin’s Sprawl and the Modern Heat Island

In contrast, Austin’s heat problem is a product of its success. As one of the nation’s fastest-growing cities, its relentless expansion has created a sprawling metropolis of heat-absorbing surfaces. Asphalt, concrete, and buildings, which constitute 30-40% of the city’s land cover, soak up solar radiation, creating a massive urban heat island effect.

On a hot day, this can translate to a stunning temperature difference. Parts of Austin, especially along the heavily developed I-35 corridor, can be 8 degrees or more hotter than the surrounding rural landscape. Nearly two-thirds of the city’s population lives within this zone of amplified heat.

Unlike Cleveland’s historical disinvestment, Austin’s challenge is managing its boom. The city is attempting to address this with a “Heat Resilience Playbook,” investing in tree planting and aiming to preserve green space, particularly in the historically underserved Eastern Crescent. However, these efforts are in a constant race against rapid development that continues to pave over the natural landscape, creating new heat-vulnerable areas.

Why Urban Design Is a National Health Issue

The experiences of Cleveland and Austin, while different in their origins, point to the same urgent conclusion: urban planning is a critical public health issue. Whether through the slow decay of discriminatory policies or the rapid growth of unsustainable development, the result is a landscape that puts the most vulnerable residents in harm’s way.

This pattern is repeated across the United States, where studies consistently find that low-income communities and communities of color have the highest exposure to the urban heat island effect. As climate change promises more frequent and intense heat waves, cities are being forced to confront their own design. Building a resilient future will require not only planting new trees but also reckoning with the historical and ongoing planning decisions that determine who is left to swelter in the heat.