WASHINGTON, DC – Under federal law, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has the authority to detain lawful permanent residents, commonly known as green card holders, under specific circumstances, prompting legal challenges from civil liberties advocates who question the policy’s constitutionality.

- The Legal Basis – The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) contains provisions that render a lawful permanent resident deportable and subject to detention for committing certain types of crimes, including “aggravated felonies” and “crimes involving moral turpitude.”

- The Constitutional Challenge – The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and other rights groups argue that these detentions, particularly when mandatory and without a bond hearing, violate constitutional protections such as the right to due process.

- Mandatory Detention – For certain offenses, the INA requires that non-citizens, including green card holders, be detained by ICE after they are released from criminal custody, often without the possibility of release on bond while they await immigration proceedings.

This complex intersection of immigration law and the criminal justice system raises significant policy questions about the rights of legal residents and the scope of executive branch enforcement power.

Why a Green Card Doesn’t Grant Absolute Immunity

A green card, which grants an individual the status of a Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR), is the primary path to U.S. citizenship. However, it does not confer all the rights and protections of citizenship. The crucial distinction lies within the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), the foundational body of U.S. immigration law.

Under Section 236(c) of the INA, ICE is mandated to take into custody any non-citizen who is removable from the country due to a range of criminal offenses. This “mandatory detention” provision applies to LPRs just as it does to other non-citizens. The list of relevant offenses is extensive and includes categories like “aggravated felonies” and “crimes involving moral turpitude.”

What constitutes an “aggravated felony” under immigration law is often broader than its traditional criminal law definition. It can include theft, fraud with a loss over $10,000, drug trafficking, and crimes of violence with a sentence of at least one year. Committing such an offense, even if it occurred years ago, can trigger detention and place a long-time legal resident into removal proceedings.

The ACLU’s Due Process Argument

The primary legal challenges to ICE’s detention of LPRs center on fundamental constitutional questions. The ACLU has filed multiple lawsuits arguing that mandatory detention policies strip individuals of their due process rights under the Fifth Amendment. Their core argument is that every person, regardless of citizenship status, is entitled to a fair hearing before being deprived of their liberty.

Legal advocates contend that holding LPRs in detention for months or even years without an individualized bond hearing is punitive, not merely a civil matter of immigration enforcement. They argue that the government must prove that an individual is a flight risk or a danger to the community to justify their continued detention. Recent court filings in cases involving detained permanent residents highlight these arguments, with lawyers stating that the government is punishing individuals before they have had a full and fair day in court. Further legal actions have focused on ensuring access to counsel, which advocates say is made nearly impossible in some detention facilities, undermining the right to a fair legal process.

The Policy Landscape and What Happens Next

When a lawful permanent resident is detained by ICE, they are typically held in a federal detention facility pending a hearing in immigration court. Unlike the criminal justice system, there is often no automatic right to a government-appointed lawyer, and the detainee faces a complex legal battle to avoid deportation, also known as removal.

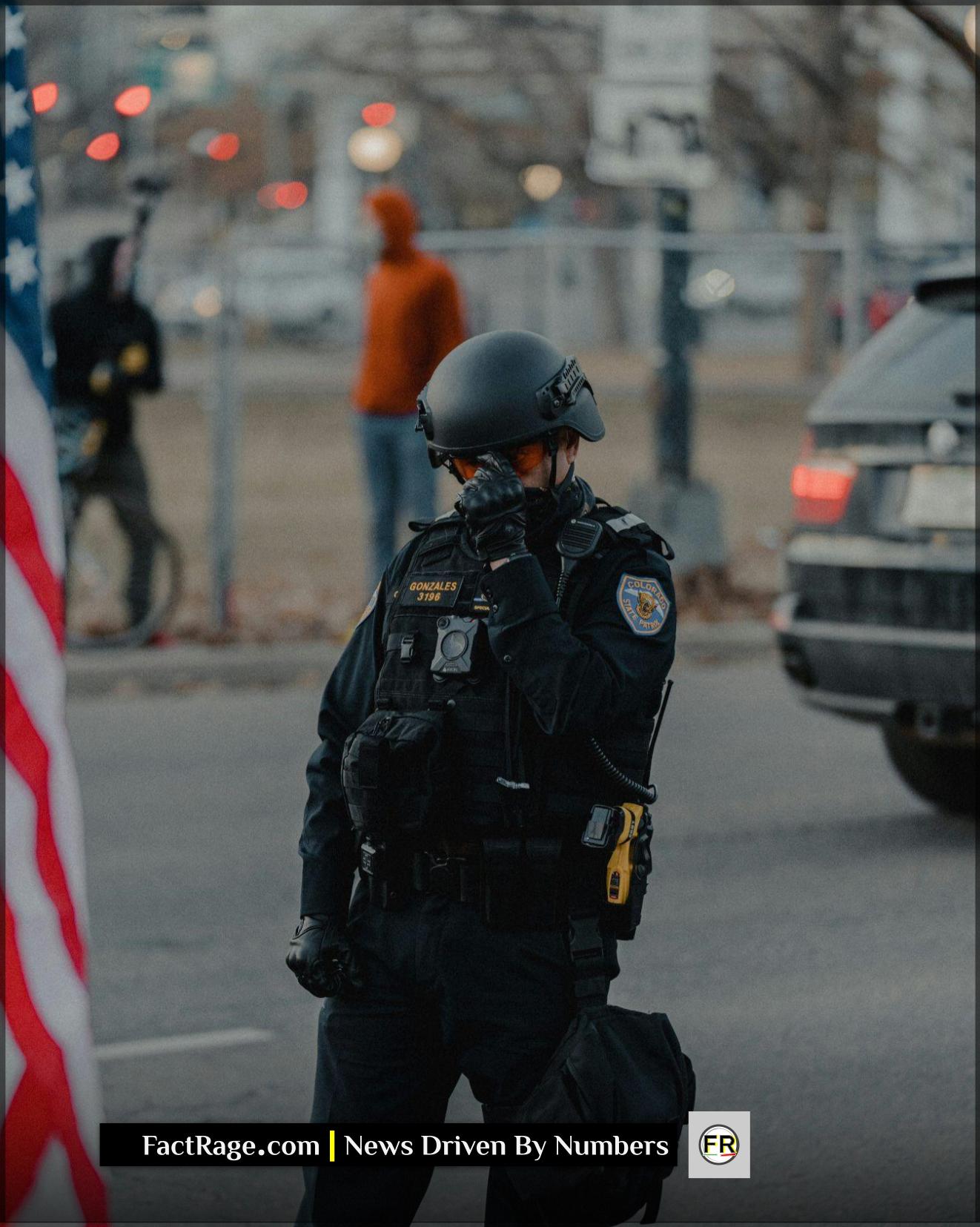

The process begins when ICE issues an “immigration detainer,” a request for a local, state, or federal law enforcement agency to hold an individual for up to 48 hours after they would normally be released, giving ICE time to take them into custody. From there, the individual’s case goes before an immigration judge. The LPR must then defend their right to remain in the U.S., while the government argues for their removal based on their past criminal convictions. The outcome can be release, continued detention, or a final order of removal, which results in the loss of their legal status and deportation. This policy framework places LPRs with criminal records in a precarious legal position, where a past mistake can unravel a life built over decades in the United States.