MONROVIA, LIBERIA – A recent viral interaction on the world stage has thrust a long-simmering domestic issue into the global spotlight, reigniting a national conversation in Liberia about its official language and what it says about the country’s identity.

- A Complicated Legacy – English is Liberia’s official language, established by the Americo-Liberians—freed and free-born American people of color—who founded the country in the 1820s.

- A Rich Linguistic Mosaic – Beyond English, there are over 20 indigenous languages actively spoken in Liberia, with Kpelle being the most widespread among them.

- The People’s Tongue – A form of pidgin English, known as Liberian Kreyol or Kolokwa, serves as the true lingua franca, used in daily communication by a large portion of the population.

This renewed focus brings to light a complex history where language is intertwined with national pride, a unique colonial legacy, and the ongoing search for a unified modern identity.

A Nation’s Voice, A Person’s Identity

![]() Language is more than a set of rules and words; it is the carrier of our history, the sound of our communities, and the shape of our identity. When a nation debates its official language, it is fundamentally asking itself, “Who are we?” The discussion in Liberia is a powerful reflection of the universal human need to see one’s own experience and heritage valued at the highest level.

Language is more than a set of rules and words; it is the carrier of our history, the sound of our communities, and the shape of our identity. When a nation debates its official language, it is fundamentally asking itself, “Who are we?” The discussion in Liberia is a powerful reflection of the universal human need to see one’s own experience and heritage valued at the highest level.

Read On…

This article delves into the personal and political dimensions of Liberia’s linguistic crossroads, exploring what is at stake for the everyday people at the heart of this national conversation.

How a Language From Abroad Became Liberia’s Official Voice

Language Families

Liberia’s indigenous languages belong to three major African language families: Mande, Kru, and Mel.

Liberia’s history is unique on the African continent. It was not a traditional European colony but a settlement established by the American Colonization Society, which promoted the “return” of free African Americans to Africa. These settlers, known as Americo-Liberians, brought their culture, religion, and language with them. They established a government modeled on that of the United States, and with it, English became the language of law, education, and power.

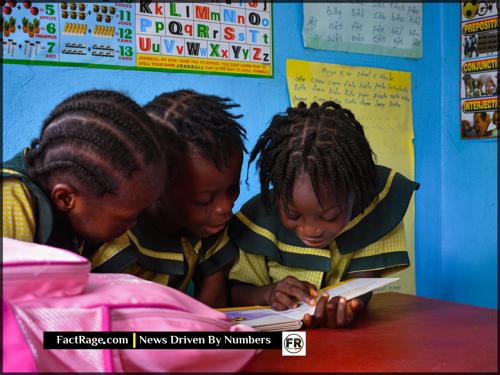

This created a socio-linguistic divide between the English-speaking ruling class and the indigenous population, who spoke a multitude of their own languages. For generations, fluency in English was a prerequisite for social and economic advancement, a dynamic that has left a lasting imprint on the nation’s cultural fabric.

What Do Most Liberians Actually Speak?

Global Context

Liberia is one of only three countries in Africa, along with Sierra Leone and the Gambia, founded as a settlement for freed slaves. This unique history directly shaped its linguistic and political structures.

Walk the streets of Monrovia or travel to the rural counties, and the dominant sound is not the formal English of government documents. It is Liberian Kreyol, or Kolokwa. This vibrant and expressive pidgin language evolved as a bridge between the English-speaking settlers and the various indigenous groups. Today, it is the most widely understood language in the country, a shared tongue that transcends ethnic lines.

Alongside Kolokwa, Liberia is home to a rich tapestry of over 20 distinct languages. Kpelle is the most spoken of these, but others like Bassa, Grebo, and Mano are central to the cultural identity of millions. This linguistic diversity poses a complex question: if an official language is meant to unify, what does it mean when the official tongue isn’t what most people speak at home or with their neighbors?

The Arguments Shaping the National Conversation

The debate over changing the official language is not new, but it has gained significant traction. Proponents of a change argue that shedding English as the sole official language is a necessary step in decolonization and in validating the cultures of the indigenous majority. Adopting an indigenous language like Kpelle, or even standardizing and elevating Kolokwa, could, they argue, foster a stronger sense of national unity and pride rooted in a shared, local identity.

However, the arguments for maintaining English are also practical and compelling. English is a global language of commerce, technology, and diplomacy, providing Liberia with a direct link to the international community. The entire legal and educational framework is built on it, and transitioning away would be an immense and costly undertaking. The challenge for Liberia is finding a path that honors its diverse heritage without isolating itself from the wider world.

The Universal Search for a Voice

![]() The story unfolding in Liberia is a profound chapter in a global narrative. Around the world, many nations and communities continue to navigate the complex legacies of their pasts. The search for an official language is ultimately a search for a collective voice—one that can honor history, reflect the present, and speak clearly to the future. It is a journey of identity that resonates far beyond the borders of this one West African nation, touching on the universal desire to define oneself on one’s own terms.

The story unfolding in Liberia is a profound chapter in a global narrative. Around the world, many nations and communities continue to navigate the complex legacies of their pasts. The search for an official language is ultimately a search for a collective voice—one that can honor history, reflect the present, and speak clearly to the future. It is a journey of identity that resonates far beyond the borders of this one West African nation, touching on the universal desire to define oneself on one’s own terms.