GLOBAL – More than half a century after the last human footsteps were left on the Moon, a new international effort led by NASA is preparing to return, this time with the goal to stay.

- A New Mission – Unlike Apollo’s goal of exploration, the Artemis program is designed to establish a sustainable, long-term human presence on the Moon to conduct science and prepare for future missions to Mars.

- Public-Private Power – Artemis relies on a mix of government-owned hardware and critical components developed by commercial partners, including a lunar lander from SpaceX and spacesuits from private industry.

- A Global Race – The program operates within a new geopolitical landscape, competing with China’s ambitious lunar exploration plans while collaborating with over 40 nations through the Artemis Accords.

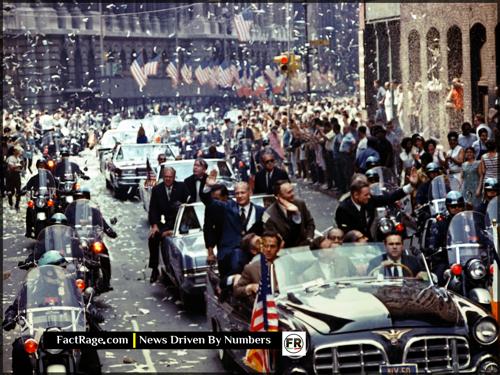

As the world marks the 56th anniversary of Apollo 11’s historic landing on July 20, 1969, the ambitions for lunar exploration are grander, the technology is fundamentally different, and the cast of players is significantly larger.

Decoding the New Moonshot

![]() The drive to return to the Moon is about more than nostalgia; it’s a calculated leap into a new technological and geopolitical era. Unlike the sprint of the Apollo years, the Artemis program is a marathon to establish a permanent human foothold off-world. This endeavor fuses government vision with commercial innovation, creating a blueprint for how humanity will explore, settle, and utilize resources beyond Earth.

The drive to return to the Moon is about more than nostalgia; it’s a calculated leap into a new technological and geopolitical era. Unlike the sprint of the Apollo years, the Artemis program is a marathon to establish a permanent human foothold off-world. This endeavor fuses government vision with commercial innovation, creating a blueprint for how humanity will explore, settle, and utilize resources beyond Earth.

Read On…

The following analysis breaks down the technology, the key players, and the strategic stakes of humanity’s return to the lunar surface.

What Makes the Artemis Missions Different from Apollo?

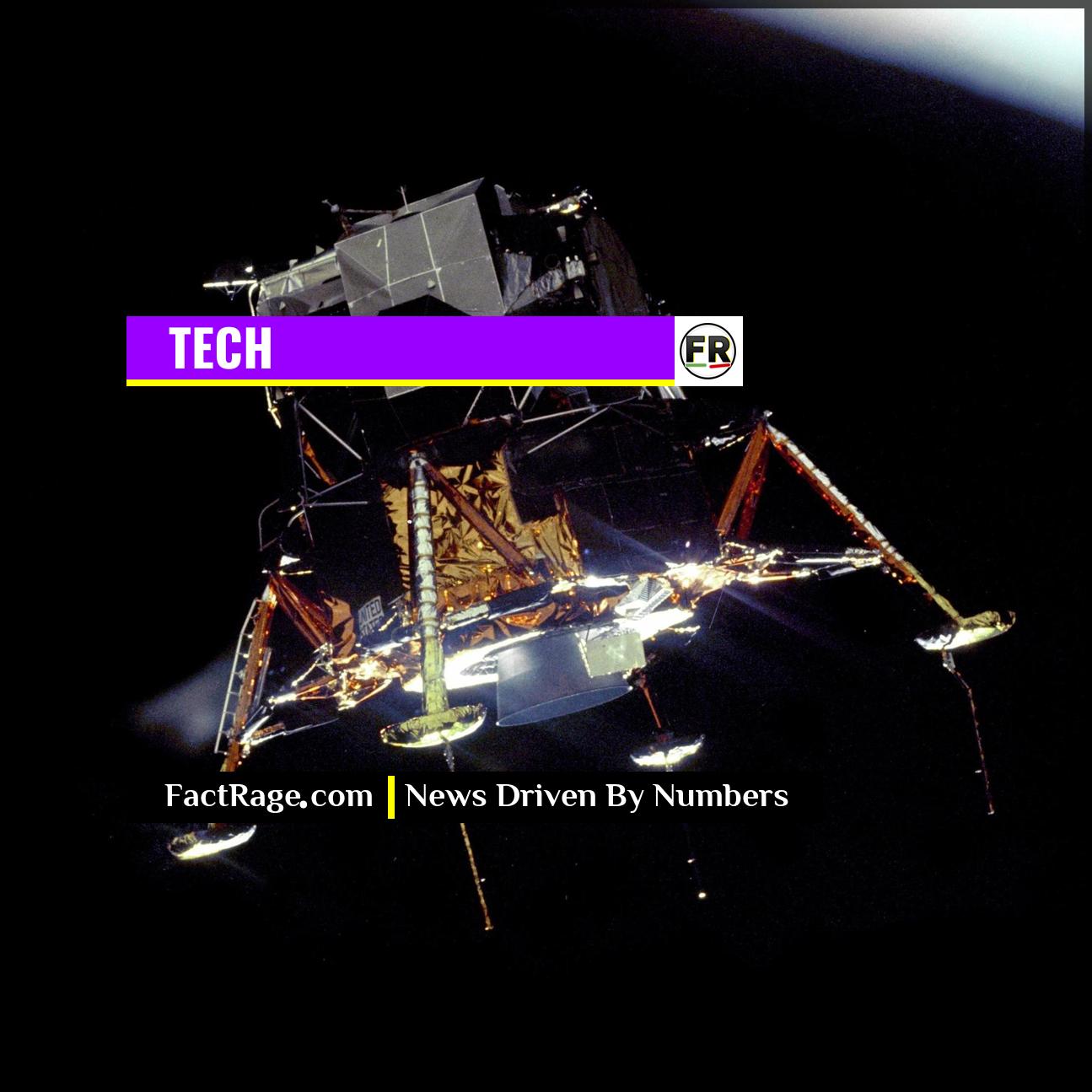

The core difference between the Apollo and Artemis programs lies in their ultimate objectives. Apollo was a sprint—a monumental technological and political achievement focused on landing humans on the Moon and returning them safely to beat the Soviet Union. Artemis, named for Apollo’s twin sister in Greek mythology, is a marathon. Its stated purpose is to build a permanent outpost for humanity on the Moon.

The plan involves a series of increasingly complex missions. Artemis I was an uncrewed test flight of the new Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion capsule, which successfully orbited the Moon in late 2022. Artemis II, currently slated for late 2025, will carry four astronauts on a lunar flyby, testing Orion’s life support systems. The pinnacle mission, Artemis III, aims to land the first woman and first person of color on the lunar surface, targeted for late 2026. What happens after that landing is key: NASA plans to build a “Base Camp” on the surface and a supporting “Gateway” station in lunar orbit, enabling long-duration stays and extensive scientific research.

The High-Tech Toolkit for a New Lunar Era

Returning to the Moon requires an entirely new generation of technology. The backbone of the program is the SLS rocket, the most powerful rocket ever built, and the Orion crew capsule, designed by Lockheed Martin for deep space missions.

However, a crucial shift from the Apollo era is the heavy reliance on the private sector for major components. The Human Landing System (HLS)—the vehicle that will actually ferry astronauts from lunar orbit to the surface—is being developed by SpaceX as a version of its futuristic Starship. A second lander is also being sourced from a team led by Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin. This competitive, commercial approach is intended to drive down costs and accelerate innovation. Even the spacesuits are being designed by private companies, a stark contrast to the government-led development of the iconic Apollo suits. Major aerospace contractors like Boeing and Northrop Grumman also remain critical partners, building the SLS core stage and solid rocket boosters, respectively.

Why Go Back? Science, Resources, and Strategy

The scientific and strategic motivations for returning to the Moon are significant. One of the primary targets is the lunar South Pole, where permanently shadowed craters are believed to hold vast quantities of water ice. Why does ice on the Moon matter so much? Water can be broken down into hydrogen and oxygen—the fundamental components of breathable air and, more importantly, rocket propellant. The ability to “mine” water and produce fuel on the Moon could revolutionize space travel, making it the first deep-space refueling station for eventual missions to Mars.

Geopolitics also plays a central role. The United States has established the Artemis Accords, a set of principles for cooperation in civil space exploration, which over 40 nations have signed. This coalition stands in contrast to a rival effort by China and Russia, which are collaborating on an International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). Both blocs are effectively in a race to establish a presence and potentially lay claim to the Moon’s most resource-rich locations. The nation or group of nations that first learns to live and work sustainably on the Moon will hold a significant strategic advantage for the future of space exploration.

From Footprints to Footholds: The Next Chapter

![]() The leap from Apollo’s fleeting visits to Artemis’s planned permanence represents a fundamental shift in our relationship with the cosmos. It’s no longer just about planting a flag; it’s about laying a foundation for science, commerce, and future multi-planetary journeys. As new technologies and global players redefine what’s possible, the next set of footprints on the lunar surface won’t just mark a destination, but the beginning of a sustained human presence beyond Earth.

The leap from Apollo’s fleeting visits to Artemis’s planned permanence represents a fundamental shift in our relationship with the cosmos. It’s no longer just about planting a flag; it’s about laying a foundation for science, commerce, and future multi-planetary journeys. As new technologies and global players redefine what’s possible, the next set of footprints on the lunar surface won’t just mark a destination, but the beginning of a sustained human presence beyond Earth.